By Mesfin Yimam, DVM, MS., Director, Pre-Clinical Research

What Is EEG and How Is It Utilized for Sleep Studies?

An EEG (electroencephalogram) is a medical device used to monitor and record the electrical activity of the brain. Small sensors (electrodes) are attached to the scalp to detect the electrical signals generated by brain cells. By analyzing the frequency and amplitude of brainwaves, sleep researchers can determine the sleep stage a person is in.¹

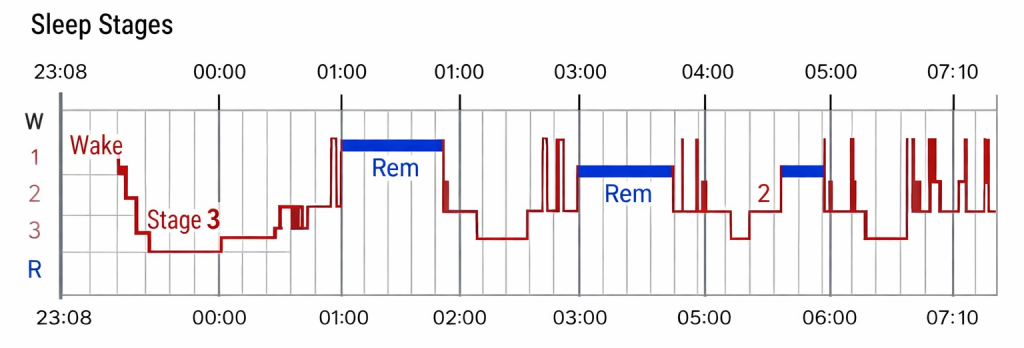

EEG data provides direct, objective insight into sleep architecture (the normal structural organization of physiological sleep), including how long it takes a person to fall asleep, the duration of various sleep stages such as light sleep, deep sleep (slow-wave sleep), and REM sleep, as well as periods of sleep interruption and wakefulness after sleep onset.

EEG devices used in polysomnography (PSG) were traditionally complex diagnostic tools for studying brain function, requiring the placement of more than ten electrodes at various locations on the scalp. Sleep studies with polysomnography had to be conducted in a sleep lab to allow for proper device placement, recording, and monitoring. However, recent technological advancements have led to the development and validation of many portable EEG devices that can be used at home with a single-channel electrode.²

Have Any Sleep Aid Ingredients Been Evaluated by EEG and What Are the Results?

Melatonin

The effect of physiological (0.1 mg and 0.3 mg) and pharmacological dosages (3.0 mg) of melatonin was evaluated using polysomnography (PSG).³ In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults over 50 with and without insomnia, a physiologic dose of melatonin (0.3 mg), taken 30 minutes before bedtime, significantly improved sleep efficiency by restoring nighttime plasma melatonin levels to those typical of younger individuals.

While both lower (0.1 mg) and higher (3.0 mg) doses showed some sleep benefits, the highest dose caused unwanted side effects, including hypothermia and prolonged elevation of melatonin levels into the daytime. Individuals without insomnia did not experience sleep improvement from melatonin supplementation.

In this PSG-monitored study, melatonin had no significant dose-related effects on total sleep time, number of awakenings, sleep onset latency, REM sleep latency, or the percentage of time spent in any sleep stage in either insomniacs or normal sleepers.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) confirmed a cause-and-effect relationship between melatonin consumption and reduction in time required to fall asleep.⁴ Consequently, a 1 mg dose should be taken before bedtime.

GABA

GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter, is commonly used as a supplement for sleep support. Its effects were evaluated using a portable EEG device following oral administration of 100 mg daily for one week in a randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial.

Results showed that GABA shortened sleep onset latency and increased total non-REM sleep time, with no significant changes in other sleep parameters. There was a non-significant reduction in REM sleep time.⁵

Valerian

Valerian, derived from the root of Valeriana officinalis, is commonly used as a herbal sleep supplement. However, objectively validated studies using EEG are limited.

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial involving older women with insomnia (average age 69), participants received 300 mg valerian extract or placebo nightly for two weeks. Sleep was assessed via polysomnography, self-reports, daily sleep logs, and actigraphy.

No statistically significant differences were observed between valerian and placebo on EEG measures such as sleep latency, wake after sleep onset (WASO), sleep efficiency, or self-rated sleep quality.⁶

L-Theanine

L-theanine is widely used as a natural sleep aid that may promote relaxation rather than directly induce sleep.⁷

In a double-blind, randomized crossover study using 100 mg of L-theanine daily for one week, no significant differences were observed in objective EEG parameters such as sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, or sleep stages. Subjective reports indicated improvement, but EEG measures did not confirm these changes.⁸

Lavender

Lavender oil has been associated with improvements in sleep quality and mood, though results are inconsistent. Some studies suggest reduced insomnia symptoms, while others indicate expectancy effects may play a larger role.

In a single-blind EEG study, lavender aroma exposure during sleep resulted in reduced alpha wave activity during wakefulness and increased delta wave activity during slow-wave sleep. However, no significant changes were observed in total sleep time, sleep efficiency, wake after sleep onset, or REM sleep.⁹¹⁰¹¹

Lime Peel

Lime peel extract standardized for hesperidin was evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 80 subjects receiving 300 mg per day for two weeks.

Polysomnography results showed reductions in sleep latency, wake after sleep onset, and total wake time, as well as increases in sleep efficiency, total sleep time, and stage 2 sleep. These improvements were not reflected in most subjective measures except reduced daytime sleepiness.¹²

Saffron

Crocetin, a bioactive compound found in saffron and Gardenia jasminoides, has been studied using actigraphy and EEG.

Portable EEG results showed increased delta power during sleep, indicating enhanced deep sleep. However, no significant differences were observed in sleep latency, sleep efficiency, total sleep time, or wake after sleep onset.¹³¹⁴

EEG Study Results for Maizinol®

The EEG device used in the Maizinol® study was an actigraphy device with EEG/EOG combination sensor from SOMNOmedics GmbH. It is a U.S. FDA 510k-registered medical device and carries EU Declaration of Conformity status.

In a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial enrolling 80 participants, Maizinol® demonstrated seven statistically significant improvements across EEG-measured sleep parameters compared to placebo:

- Shortened sleep onset latency

- Reduced wake time after sleep onset (WASO)

- Reduced nighttime awakenings

- Increased REM sleep

- Increased NREM sleep

- Increased total sleep time

- Improved sleep efficiency

This standardized corn leaf extract improved sleep continuity and architecture as measured by EEG/EOG.¹⁵

Participants also reported significant improvements in subjective sleep quality as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), including improvements in global score, sleep quality, duration, latency, and daytime dysfunction.

Why EEG is the Gold Standard for Clinical Substantiation of Sleep Aid Benefits

Many sleep aid supplements rely primarily on subjective measures such as PSQI or actigraphy without EEG confirmation.

Studies comparing PSQI with EEG-derived sleep stage data found that objective measures such as wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, and total sleep time correlated with specific PSQI components. However, PSQI total score did not correlate with objective EEG metrics.¹⁶

Consumer sleep-tracking devices have shown reasonable performance in detecting sleep but inconsistent results in sleep stage assessment and lack validation across populations.¹⁷

EEG serves as a confirmatory measure. Some supplements with positive subjective reports have shown no meaningful EEG effects or even worsening sleep maintenance when objectively measured.

Conclusion

Maizinol® represents a new benchmark in science-based natural sleep support. With seven EEG-confirmed objective improvements validated by subjective PSQI improvements and a melatonin-enabling mechanism that preserves circadian integrity, Maizinol® offers evidence-based, clinically substantiated sleep support.

References

- C.J. de Gans et al. Sleep assessment using EEG-based wearables – A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews 76 (2024) 101951.

- Manal Mohamed et al. Advancements in Wearable EEG Technology for Improved Home-Based Sleep Monitoring and Assessment. Biosensors 2023, 13, 1019.

- Zhdanova IV et al. Melatonin treatment for age-related insomnia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(10):4727-30.

- European Food Safety Authority. EFSA Journal. 2011;9:2241.

- Yamatsu A et al. Effect of oral GABA administration on sleep. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2016;25(2):547-551.

- Taibi DM et al. A randomized clinical trial of valerian. Sleep Med. 2009;10(3):319-28.

- Bulman A et al. Effects of L-theanine consumption on sleep outcomes. Sleep Med Rev. 2025;81:102076.

- Tominaga T et al. Low dose theanine and sleep. Food Sci Nutr Res. 2022;5(1):1-7.

- Chien LW et al. Lavender aromatherapy and insomnia. 2012.

- Howard S & Hughes B. Lavender expectancy effects. 2008.

- Ko LW et al. Essential oil aroma and slow-wave EEG. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1078.

- Kim S et al. Standardized lime peel supplement and sleep. Phytomedicine. 2025;139:156510.

- Kuratsune H et al. Crocetin and sleep. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(11):840-3.

- Umigai N et al. Crocetin and sleep quality. Complement Ther Med. 2018;41:47-51.

- Yimam M et al. Standardized corn leaf extract and sleep. Sleep 2025.

- Zitser J et al. PSQI responses and objective sleep measures. PLOS ONE. 2022.

- Chinoy ED et al. Consumer sleep-tracking devices vs polysomnography. SLEEPJ. 2021;44(5):1-16.